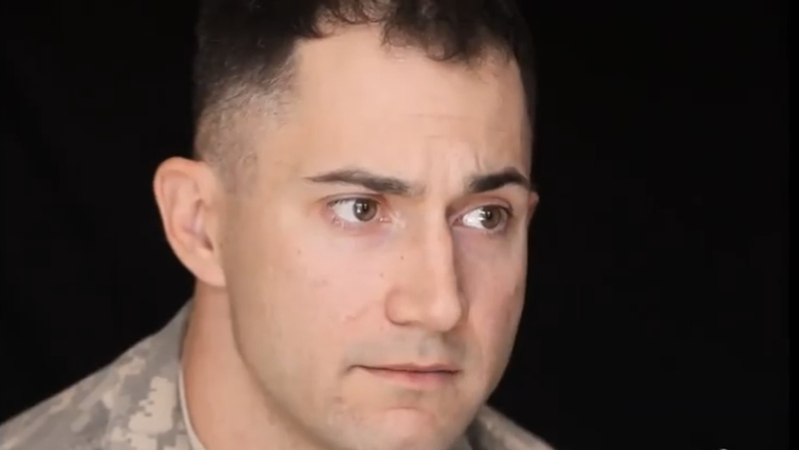

I first met Adrian Bonenberger in 2014, after he completed two tours in Afghanistan. He’d published Afghan Post, a painful epistolary memoir about his experiences. Bonenberger started that book a breezy, confident, idealistic young officer, but as he came across more cruelty, waste, and corruption, started to break down, second-guessing not only the mission but himself, i.e. why he’d volunteered.

At the outset of Afghan Post Bonenberger referenced everything from the illustrated versions of The Odyssey and The Iliad he read as a kid, to All Quiet on the Western Front. But after years of head-scratching missions, circuitous contracting schemes, and lies sent down from above (and demanded in return), he seemed to realize, unpleasantly, that his experience was less Homer and more Catch-22.

He laughs some, but mostly the absurdity crushes him. A selection of passages gives a snapshot of his progression:

My life is in near-perfect harmony… This is what I’ve been aiming for, a sense of balance, of co-existing with the world. My job at this instant is precisely what it needs to be, no more, no less. I’m a good commander, man… Life feels correct.

We aren’t here to defeat the enemy; that’s impossible with our resources. We’re here to occupy them, to distract them from the women wearing blue jeans in Kabul.

No matter how many rifle-bearing insurgents we kill, they only seem to increase in numbers and proficiency.

I just want to keep bashing away at the Taliban until they quit. I refuse to stop. I will break them with constant patrolling…

What are we doing. This makes no sense. I feel my grasp on humanity slipping away. The army believes the solution to this is behavioral health. We’d do better with some religious/moral equivalent — sadly, our own multi-faith shepherd/ expert does not provide me with anything like the type of certainty I’d need to get me through this or buck-up.

He unravels, and as the diary goes on, seems to become more concerned with his own mental survival than with making sense of the mission, which becomes little more than an absurdist plot point. By the end, he writes, “Afghanistan is sending me out, as though I never set foot here, utterly unchanged,” adding:

The landscape is so harsh and unforgiving — on the one hand, the people I see trying to drag a living from the dust seem like heroes or madmen — on the other hand, they move slowly and without obvious desperation — it’s only after a great deal of time spent around them that you realize this transcends the fatalist predisposition of their culture… These people are the embodiment of despair; life without hope of improvement, waiting for an early death from disease, accident, or murder.

Can’t wait to leave this place and these thoughts behind.

I thought of Adrian after Joe Biden announced that “I have concluded that it’s time to end America’s longest war.” The question that faded from view by the end of Adrian’s two tours was one of the first Biden addressed.

We went to Afghanistan, President Biden said, “to ensure Afghanistan would not be used as a base from which to attack our homeland again.” And “we did that. We accomplished that objective.”

Is that true? Less than a day after Biden’s speech, even would-be allies of the administration like former Clinton adviser Richard Clarke were saying that there was a “high probability” the Afghan government would fall, and Westerners would soon be chased out by the Taliban, in scenes likely to recall the scrum for helicopter seats in Saigon in 1975.

Is Clarke wrong? If not, what was the point? Was there ever one? I asked Adrian’s perspective, as a former soldier.

Read the rest of this article at Matt Taibbi’s Substack